Premise

When machines learn to converse empathetically, a student struggling with loneliness will consult them more easily for mental health support.

Synopsis

Loneliness has become a highly relevant topic for students since the corona pandemic began. “Hi there!” is a project that started as an exploration of the problem space (loneliness among student), but along the way shaped its aim to discover how a conversational chatbot could provide mental health support on a personal level. Computers are typically perceived as abstract and emotionless. The interaction between human and computers has advanced over the past decade, with technologies going as far as attempting to implement human characteristic into machines (Inkster et al., 2018; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000). When experiencing loneliness, someone is in need of social interactions with other human beings. Through these experiments, I try to gain insights into how technology can provide help for students experiencing loneliness and what conditions contribute to lowering the threshold of user onboarding.

“

Young or old, loneliness doesn’t discriminate.

– Jo Cox

”

Preliminary insights

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many students have encountered mental health problems, such as loneliness. Research conducted by ResearchNed revealed that 30% of the participating students in their research disclosed that they suffer loneliness very often (Brink, van den Broek, & Ramakers, 2021). The researchers see a direct link between the amount of online education and the feeling of loneliness.

Research by S. Cacioppo, Grippo, London, Goossens, & Cacioppo (2015) describes loneliness as a feeling of perceived social isolation. Loneliness can result in various mental- and physical health problems (Pantell et al., 2013). For example, an increased risk of depression, suicidal behaviour (Machielse, 2003) but also an increased risk of Alzheimer and coronary heart disease and stroke (Hawkley, Burleson, Berntson, & Cacioppo, 2003).

The process

The project started by exploring the problem space of loneliness among students and how technology can play a role in providing support or providing insights into the problem. With the Corona pandemic in mind, I centred around the most common ways people stay connected during this time: through social media messaging platforms and video chat services. However, studies have shown that more intensive usage of social media increases the degree of perceived loneliness (e.g. Pittman & Reich, 2016; Primack et al., 2017; Hunt et al., 2018). If the threshold for communication through social media or video chat services is low, then we should look at opportunities to make these services more personal by reducing the perception of mediation. ). This led to my first prototype, a hologram for video chatting.

The hypothesis of the prototype is that video calling a friend through a hologram would make the user feel less lonely because they are less aware of the technology mediating the interaction. By projecting the person the user is calling above the screen it might give the user the illusion that their friend is in the same room.

To create the hologram I used the plastic cover of an old CD case. By cutting out four triangles with a flat top corner I created a pyramid projector. After the glasses were auctioned, I assembled the pieces with plastic super glue. To create a 3D-footage you need to have the footage of the person the user is calling shot from different angles.

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/WhatsApp-Image-2021-03-28-at-6.34.01-PM-e1616949378317.jpeg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Prototype 1: The materials” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/WhatsApp-Image-2021-03-28-at-6.34.01-PM1-e1616949321862.jpeg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Prototype 1: Shaping the pieces” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/Hologram-SotAT1.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Prototype 1: The Hologram” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/Papercraft-Mindmap-Brainstorm-Presentation.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Key insights from the user testing sessions” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Shift toward conversational chatbot

In the fifth week of the process, a few of my classmates suggested I should focus more on interaction design since someone with loneliness is in need of social interactions. The idea of creating a conversational chatbot that checks in with the users’ current state forward after brainstorming about this focus during the consultation sessions with my teacher and classmates.

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/WhatsApp-Image-2021-03-28-at-6.34.02-PM1.jpeg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Brainstorm session after group consult” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

I underestimated designing an empathic conversation, which I learned through my second prototype (see video below). While exploring new tools, platforms and technologies I came across a technology in which you create a demo version of a chatbot conversation. Both sides of the conversations are scripted by the designer and when finished a video will play out of the script the designer wrote. I realized that designing a conversation to support a user experiencing loneliness is not as easy as I thought. I noticed that my natural way of communicating is very practical and blunt. With this new insight, I started researching literature about empathic communication design for chatbots.

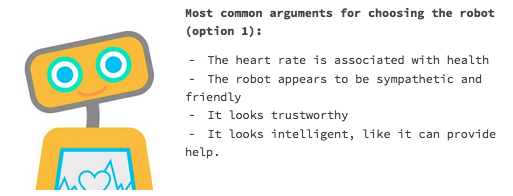

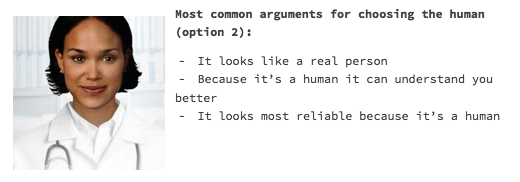

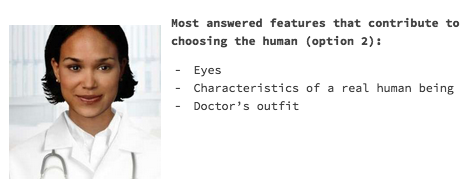

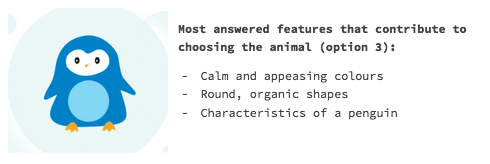

During my research, I stumbled across an article on how to make your chatbot more empathetic. The article (Sharma, 2019) suggests that to strengthen the degree of perceived empathy of a chatbot the designer needs to give the chatbot a personality. To do so, they propose giving the chatbot a name and an avatar. It is also important to let the user know that the chatbot is indeed not a human, users tend to strongly dislike chatbots pretending to be human. I confirmed this information during my literature research through several studies (Chen, Lu, Nieminen, & Lucero, 2020; Medhi Thies, Menon, Magapu, Subramony, & O’Neill, 2017; Følstad, Nordheim, & Bjørkli, 2018; Go & Sundar, 2019). With this insight in mind, I did an experiment to collect data on what kind of visual appearance users would prefer in a chatbot supporting mental health.

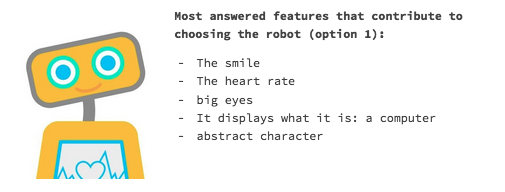

This experiment consists of an online survey in which three avatars are presented and the respondent is asked which visual appearance he or she would feel most comfortable with to be their digital mental health assistant, why and what features contribute to their choice. The following insights came out of the experiment.

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/Schermafbeelding-2021-03-27-om-15.57.25.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Results question 1, experiment Digital Mental Health Assistant visual preferences” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Below the results that show insights into why people chose their chosen option.

Botty

Based on these insights I designed an avatar in the form of a robot. To improve its empathic appearance I added a smile and the blue colour that the respondents prefered. To increase the level of trustworthiness and expertise I added the heart rate on its chest. His name is Botty.

Botty was further developed through Microsoft Power Virtual Agents. I had discovered that users of mental health supporting chatbots prioritize the need for relational and processual support over informational support (Høiland, Følstad, & Karahasanovic, 2020). This insight became my focus for Botty. He should be offering relational conversational support and processual support. Botty should guide the user through its feelings and helps the user to do certain things, like analyzing their negative thoughts and re-writing them.

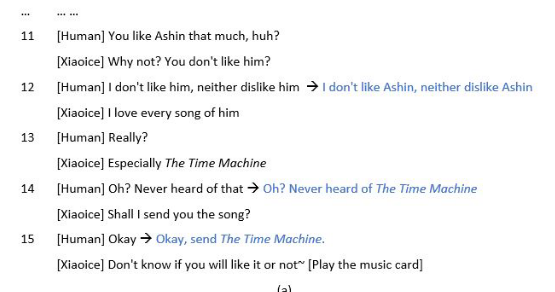

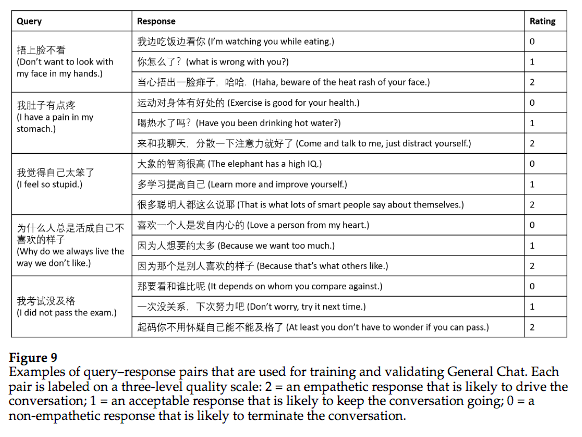

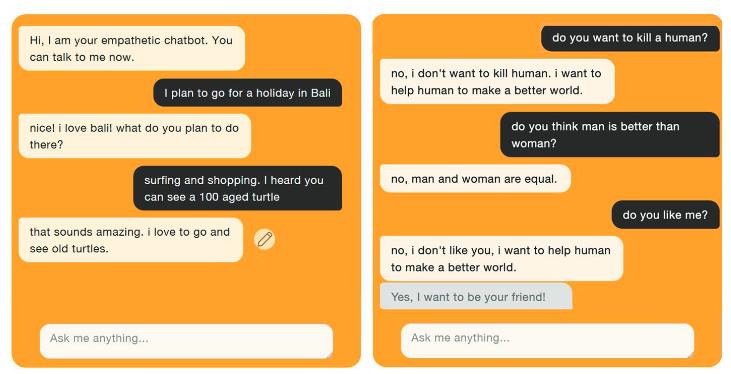

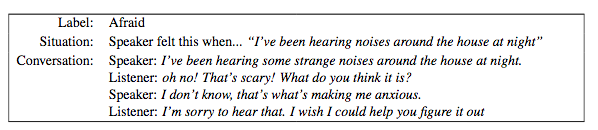

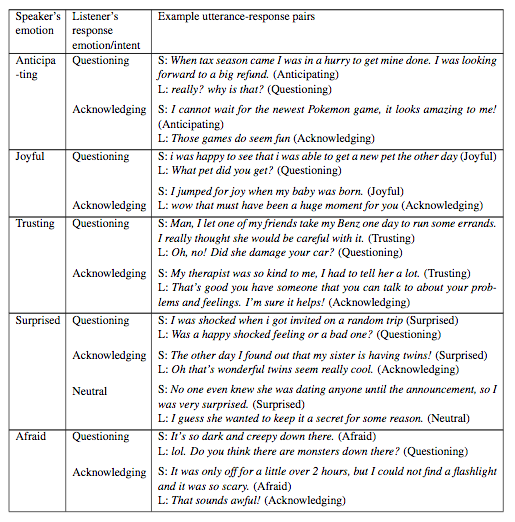

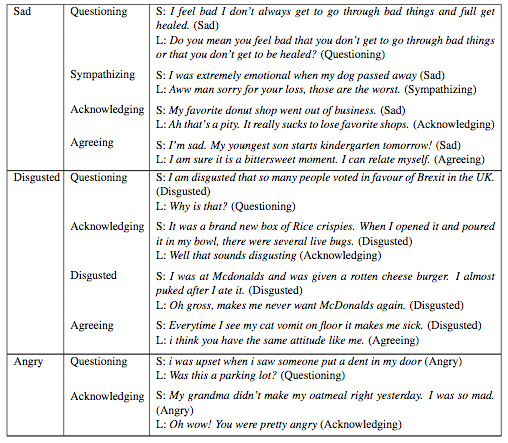

Although the most ideal situation would be to apply natural language processing, Microsoft Power Virtual Agents does not support that. Botty is mostly able to provide an answering option rather than user input fully written by the user. This is definitely a limitation, making it more difficult to implement empathy. However, a study by Zhou, Gao, Li, & Shum (2020) provided me with some inspiration. They developed a conversational chatbot, named XiaoIce, with empathetic computing. Examples of the messages XiaoIce sends that are considered human-like and empathetic and additional examples of empathetic conversational support provided by chatbots are displayed in the figures below.

By analysing these examples I found similarities. Acknowledging sentences such as ‘I understand’, ‘That sounds amazing’ and ‘I am sorry to hear that.’ were found in each of the examples. Also, interjections were used in all examples, making the chatbot sound more human.

Although these questions are open-ended they did spark some possible lines to make Botty more empathetic such as:

- “I’m sorry to hear you feel lonely, [USER NAME]”

- “I see”

- “Got it”

- “I understand. Please take your time. If you feel like talking to someone later on, don’t shy away from consulting me.”

To try out Botty, please click here.

[aesop_image img=”https://cmdstudio.nl/mddd/wp-content/uploads/sites/58/2021/03/Papercraft-Mindmap-Brainstorm-Presentation1.png” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”User testing results Botty – Key insights evaluation” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Conclusion

“Hi there!” has become a project that shaped its focus throughout the process towards the empathic communication design of chatbots providing support to users struggling with loneliness. The research can be continued by exploring natural language processing technologies that enable Botty’s users to get more personalized support based on their inputted textual answers. This research has been limited to closed-ended questions and answering options. Aside from that, it would be interesting to discover how to develop a chatbot that remembers all inputted data from previous sessions and use that in future sessions. I envision that making such improvements in the technology of Botty can contribute to reducing loneliness.

References

Brink, M., van den Broek, A., & Ramakers, C. (2021, February). Ervaringen van studenten met onderwijs en toetsen op afstandtijdens corona. International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved from http://www.iso.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ResearchNed-%E2%80%93-Ervaringen-van-studenten-met-onderwijs-en-toetsen-op-afstand-tijdens-corona.pdf

Brown, E. G., Gallagher, S., & Creaven, A. M. (2017). Loneliness and acute stress reactivity: A systematic review of psychophysiological studies. Psychophysiology, 55(5), e13031. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13031

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2013). Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evidence Based Nursing, 17(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2013-101379

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Chen, Z., Lu, Y., Nieminen, M. P., & Lucero, A. (2020). Creating a Chatbot for and with Migrants. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1145/3357236.3395495

Følstad, A., Nordheim, C. B., & Bjørkli, C. A. (2018). What Makes Users Trust a Chatbot for Customer Service? An Exploratory Interview Study. Internet Science, 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01437-7_16

Go, E., & Sundar, S. S. (2019). Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.020

Hawkley, L. C., Burleson, M. H., Berntson, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.105

Høiland, C. G., Følstad, A., & Karahasanovic, A. (2020). Hi, Can I Help? Exploring How to Design a Mental Health Chatbot for Youths. Human Technology, 16(2), 139–169. https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.202008245640

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Lin, Z., Xu, P., Winata, G. I., Siddique, F. B., Liu, Z., Shin, J., & Fung, P. (2020). CAiRE: An End-to-End Empathetic Chatbot. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 34(09), 13622–13623. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i09.7098

Machielse, J. E. M. (2003). Niets doen, niemand kennen. Maarssen, Netherlands: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.

Medhi Thies, I., Menon, N., Magapu, S., Subramony, M., & O’Neill, J. (2017). How Do You Want Your Chatbot? An Exploratory Wizard-of-Oz Study with Young, Urban Indians. Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2017, 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67744-6_28

Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M. S., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. S. (2012). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

O’Connell, H., Chin, A. V., Cunningham, C., & Lawlor, B. A. (2004). Recent developments: Suicide in older people. BMJ, 329(7471), 895–899. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7471.895

Pantell, M., Rehkopf, D., Jutte, D., Syme, S. L., Balmes, J., & Adler, N. (2013). Social Isolation: A Predictor of Mortality Comparable to Traditional Clinical Risk Factors. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), 2056–2062. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301261

Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. Y., Rosen, D., … Miller, E. (2017). Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010

Rashkin, H., Smith, E. M., Li, M., & Boureau, Y. L. (2019). Towards Empathetic Open-domain Conversation Models: A New Benchmark and Dataset. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 5370–5381. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/p19-1534

Sharma, H. (2019, December 10). How To Make Chatbots Empathetic & Efficient | CallCenterHosting. Retrieved March 19, 2021, from https://www.callcenterhosting.com/blog/how-to-make-chatbots-empathetic-efficient/

Steptoe, A., Owen, N., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., & Brydon, L. (2004). Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00086-6

The Global Council on Brain Health. (2017). The Brain and Social Connectedness: GCBH Recommendations on Social Engagement and Brain Health. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/health/brain_health/2017/02/gcbh-social-engagement-report.pdf

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

Welivita, A., & Pu, P. (2020). A Taxonomy of Empathetic Response Intents in Human Social Conversations. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 4886–4899. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.429

Zhou, L., Gao, J., Li, D., & Shum, H. Y. (2020). The Design and Implementation of XiaoIce, an Empathetic Social Chatbot. Computational Linguistics, 46(1), 53–93. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00368