Premise

A conversational agent to make students with anxiety feel comfortable to self-disclose.

Synopsis

Students with anxiety have a harder time self-disclosing to others. Anxiety can cause individuals to avoid social encounters, expect negative evaluations, and disclose less personal information. On the other hand, self-disclosure is critical for developing an identity, self-worth, and overall well-being, especially during adolescents. Nowadays, students self-disclose regularly on social media. This brings the benefits of self-disclosure, but it can also negatively affect students’ mental health. Especially people with pre-existing anxiety are online most heavily affected by behaviors such as seeking validation, fearing judgment, comparing, and cyberbullying. To take away the negative effects, conversational agents have the potential to facilitate an online environment for students with anxiety to self-disclose. A chatbot can encourage users to share their thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment or public exposure.

Substantiation

Self-disclosure is sharing personal information about oneself with others. This process is critical during adolescence, as it is the time when people start to develop relationships, define their identity, and acquire a feeling of self-worth and overall well-being (Vijayakumar, 2020). The process of self-disclosure varies depending on several variables, such as the audience, depth, amount, and type of information shared. Hang Chu (2022) argues that the quality of self-disclosure, such as the truthfulness of the information disclosed, is more meaningful than the frequency.

Anxiety-prone students may experience increased anxiety and avoid social situations that may lead to evaluation by others, according to Hur et al. (2019). Zhang et al. (2021) adds that people with anxiety often expect negative evaluations from others. Despite the mood-enhancing effects of being around close friends, socially anxious individuals are less likely to spend time with them and anxiety is linked to a general decrease in mood (Hur et al., 2019).

According to Popat (2022), the majority of students regularly disclose themselves on social media, which brings the benefits of self-disclosing. However, using social media can harm students’ mental health as well, particularly those who already have anxiety. Social media use has the potential to encourage certain behaviors, including seeking approval, comparison, fear of judgment, and cyberbullying (Popat, 2022).

Ho (2018) argues that conversational agents offer advantages over human partners in self-disclosure. Research indicates that self-disclosure with chatbots has the same positive effect as self-disclosure with humans. People avoid disclosing to others for fear of negative feedback, but chatbots offer a non-judgmental environment.

According to Angenius (2023), using dialogue journaling is an approach to engage with someone’s disclosure. He adds that using a chatbot can inspire students to share their information in a private context. By using chatbots for journaling, anxious students may feel more comfortable disclosing sensitive information to a non-judgemental agent.

This project explores self-disclosure to a chatbot through ideation and prototyping of a ‘journal’ experience. When a student has anxiety, sharing information with humans can be challenging. The chatbot aims for the user to feel comfortable disclosing to the chatbot as if it were a friend.

Prototype and experiments

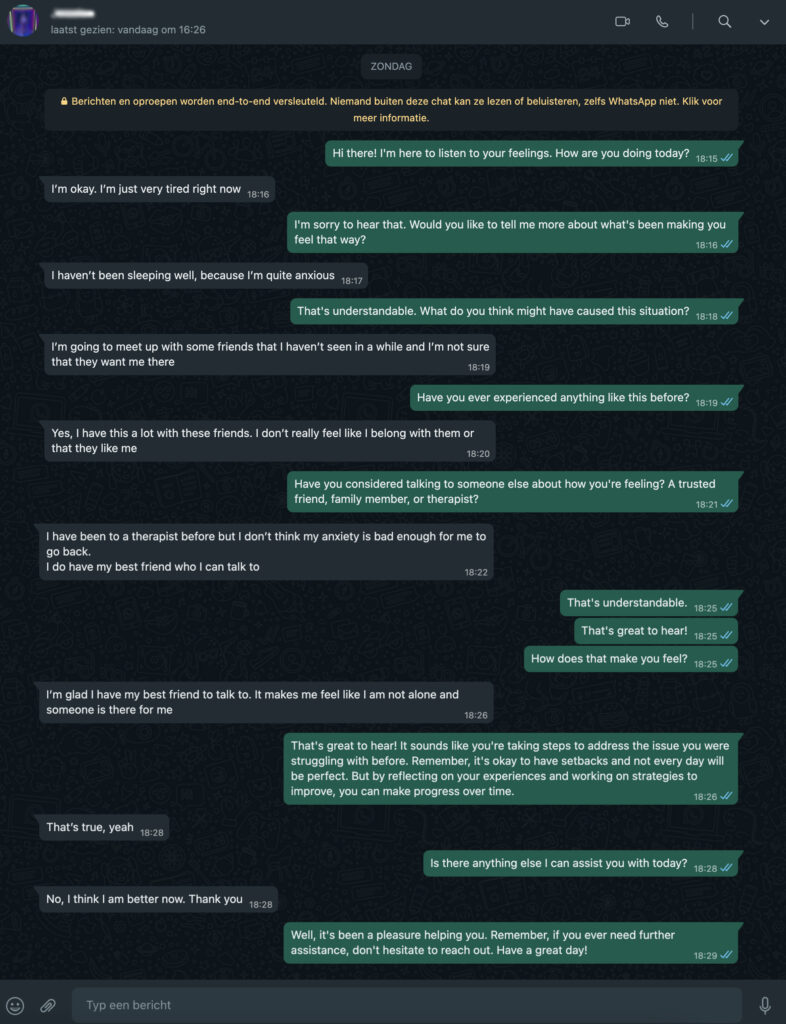

The conversational agent, a chatbot, will be prototyped and iterated based on user tests with students with anxiety between 18-25. For the first experiment, I used the Wizard of Oz method, which involves simulating the chatbot’s functionality that is controlled by a human (Ramswamy, 2022).

I tested a conversation with three participants to determine whether this concept was effective. The users could chat on their phones via WhatsApp, and I (the chatbot) could only respond with pre-defined answers or questions.

The feedback on the concept of the chatbot was positive, and the users felt that a chatbot could be helpful to talk about feelings. This experiment also showed that the chatbot lacked dept. One participant said the conversation was more like an interview. The next prototype should be more dynamic such as responding in various ways and being able to understand the context of the conversation.

Iteration 1

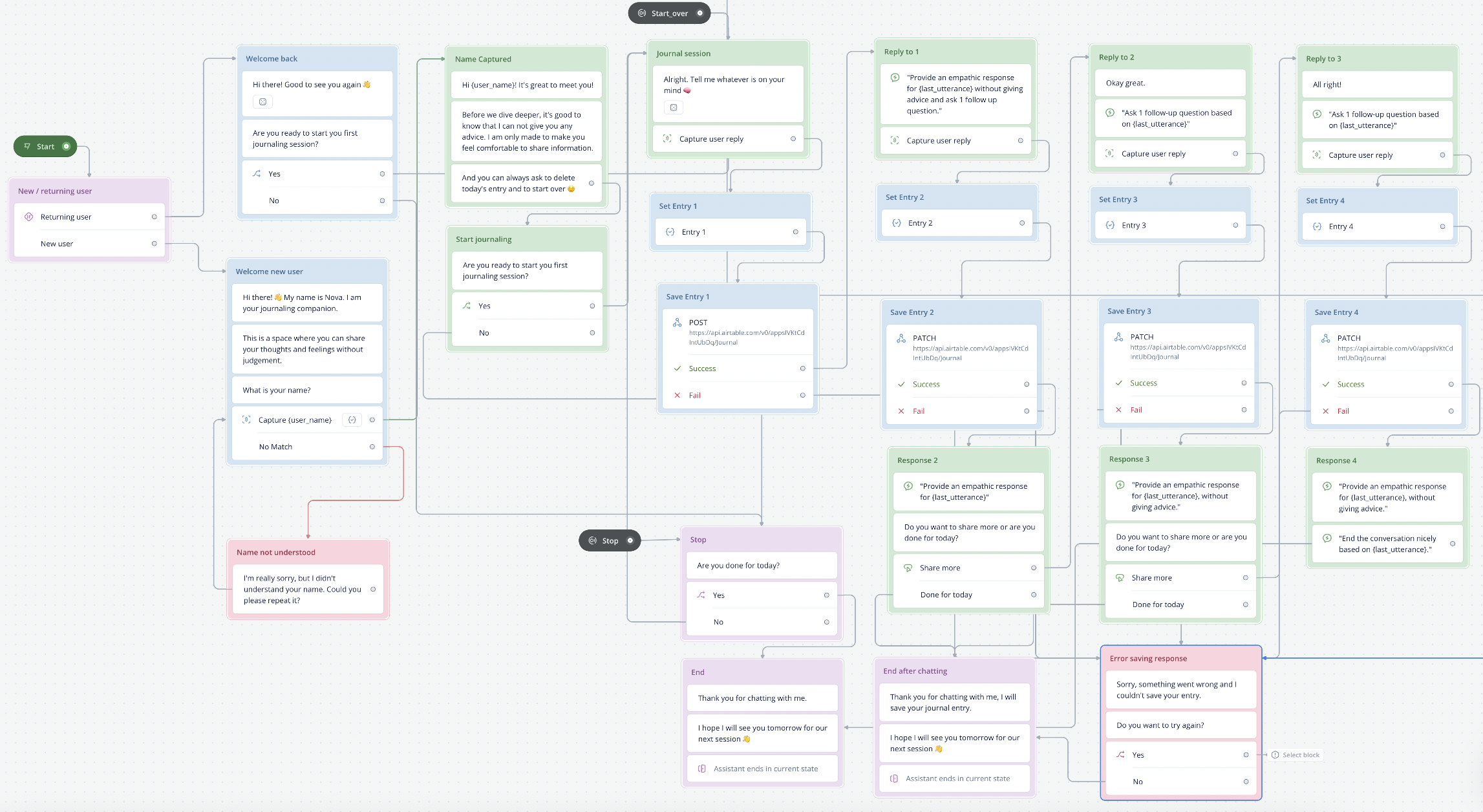

For the prototype, I used Voiceflow, a platform for building complex conversational experiences. I started by understanding the features of intents, capture, and logic. I added utterances and entities and trained the NLU model from Voiceflow to understand human language. The following elements were created:

- Introduction: explaining the chatbot’s purpose and make the user comfortable by clarifying that this space is safe.

- Clear boundaries: telling the user what the chatbot can and cannot do.

- Basic chatbot requests: ask to start over and end the conversation based on intents.

- Creating the happy path: the basic flow of the user. Responding to utterances according to positive or negative emotions.

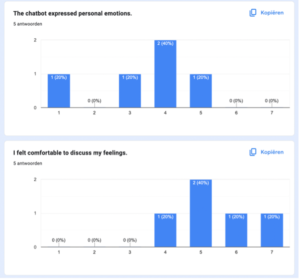

I tested the prototype with five participants. After the session, they answered a survey. Based on the 7-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Users gave brief responses to the chatbot and did not share very personal information, despite claiming to feel comfortable discussing their feelings in the questionnaire. In addition, errors were found in the chatbot’s responses, such as failure to recognize names and limited emotional recognition, which in some cases led to illogical responses. These issues will be addressed in the next iteration.

Iteration 2

Based on the feedback, I made a second iteration to make the chatbot more human-like, with the goal of letting the users open up more.

- A feeling of a friend: the chatbot got a name, and I added emojis.

- Name recognition: I added 2000 dutch names to the NLU.

- Returning user: remembering the user by adding returning user path.

- Saving data: I used the API feature to connect the chatbot to the Airtable* database to save the user responses.

- AI-response: The chatbot’s responses were limited to ‘Positive’ and ‘Negative’ emotions, but user testing showed the need for more specific responses. To address this, I added AI response prompts using Large Language Models (LLM) to generate contextual text. This allowed the chatbot to respond in a more personalized way and ask follow-up questions to encourage users to share more information.

I tested the prototype with three participants and interviewed them after the session about their experience. The chatbot was able to have a comprehensive conversation, and users appreciated the empathic responses and follow-up questions. For the next iteration, I will also add this to the introduction.However, I discovered some errors and limitations in the chatbot’s functionality and plan to improve it by implementing more intent options. Additionally, ethical considerations are crucial now that the chatbot is integrated with another platform. It should avoid offering advice or assuming the role of a therapist but instead act as a supportive listener.

Iteration 3

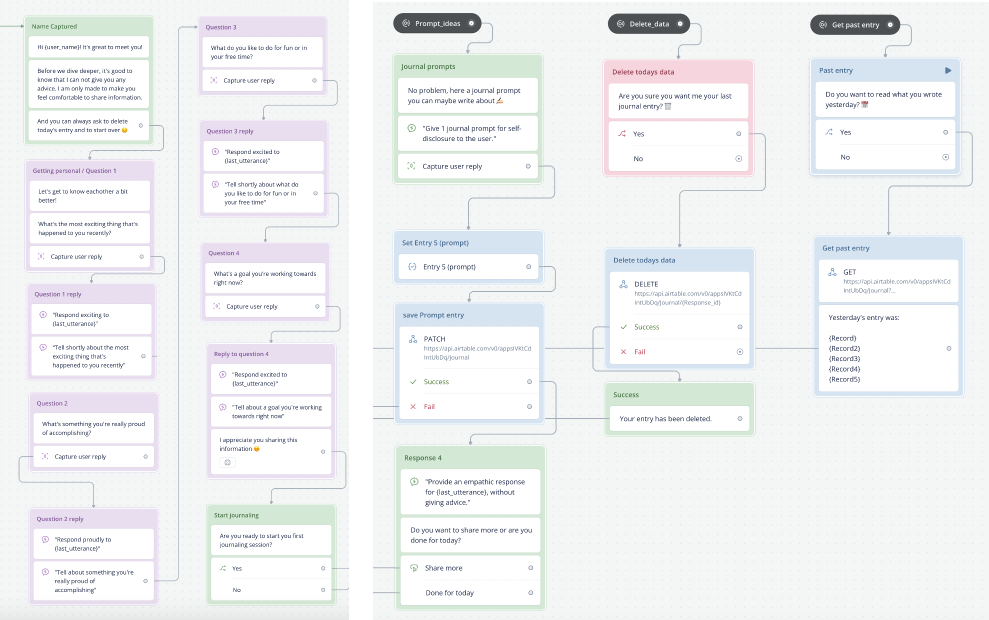

Based on the feedback, I made a third iteration. The following elements were updated or added:

- Privacy/control: getting and deleting the last entry from the database.

- Dynamic paths: adding journal prompts for the user in case they do not know what to write.

- Expanding the introduction: more questions and responding with empathy to let the user feel more comfortable sharing information.

- Chatbot disclosure: Including disclosure in the chatbot’s responses makes the exchange feel more conversational.

- Fixing errors: uncommon phrases, paths, or repeating.

. .

Despite the improvements of more extended conversations in the previous user tests, some depth is still lacking in the self-disclosure. According to the social penetration theory from psychologists Altman and Taylor (1973), relationships deepen over time through self-disclosure. So, in the next prototype, I tested with a participant not once but for a few days in a row to see if the conversations deepened after multiple sessions.

Screen recordings of the transcripts:

The first session.

The fifth session.

The tests show that the user started with short and closed answers and actually opened up more over time. Later, the user explored more paths and used prompts. Despite some progress in self-disclosure, there is still potential for improvement. Further testing is needed to identify other potential factors that might influence the prototype’s ability to facilitate deeper conversations.

Conclusion

This research indicates that the functionality of the chatbot has been improved to make the user feel more comfortable to self-disclose. The tests show that the users are not likely to express personal information instinctively. So, it is essential to encourage users to self-disclose more deeply. Besides that, empathy and human-like behavior are needed to make the user comfortable. Another factor to keep in mind, the users’ awareness that their responses are being used for the project may limit their disclosure of sensitive information. In future research, doing a longitudinal study to examine the long-term behavior is interesting. It would also be crucial to interview experts about privacy and ethical considerations to ensure that the user won’t be harmed.

* Note on Airtable, considering privacy.

The users personal information is stored so this must be handled responsibly. According to Airtable, they use encryption for all data at rest to protect the user data. Airtable has a privacy policy that they do not sell or share user data with third parties and users have the right to delete all their data permanently.

References

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York, NY: Holt.

Angenius, M., & Ghajargar, M. (2023, January 1). Interactive Journaling with AI: Probing into Words and Language as Interaction Design Materials. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Science+Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25581-6_10

Chu, T. L., Sun, M., & Jiang, L. J. (2022, August 9). Self-disclosure in social media and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships; SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221119429

Ho, A. S., Hancock, J. T., & Miner, A. S. (2018). Psychological, Relational, and Emotional Effects of Self-Disclosure After Conversations With a Chatbot. Journal of Communication, 68(4), 712–733. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy026

Hur, J., DeYoung, K. H., Islam, S., Anderson, A. S., Barstead, M. G., & Shackman, A. J.(2020). Social context and the real-world consequences of social anxiety. Psychological Medicine, 50(12), 1989–2000. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719002022

Popat, A., & Tarrant, C. (2022, June 7). Exploring adolescents’ perspectives on social media and mental health and well-being – A qualitative literature review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry; SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221092884

Ramaswamy, S. (2022, november). The Wizard of Oz Method in UX. NNgroup. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/wizard-of-oz/

Vijayakumar, N., & Pfeifer, J. H. (2020, 1 February). Self-disclosure during adolescence: exploring the means, targets, and types of personal exchanges. Current opinion in psychology; Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.005

Zhang, I., Powell, D. E., & Bonaccio, S. (2021, December 16). The role of fear of negativeevaluation in interview anxiety and social‐evaluative workplace anxiety. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 30(2), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12365