Premise

Encouraging young adults to better understand how their relationship with their environment affects their risks during a flood by creating an interactive story with Streamlit and a Recommender System.

Synopsis

Residents of the Netherlands are at risk of experiencing coastal and river flooding. If such a situation arises, it is important to take the right actions to stay safe. Young adults are at risk of acting inappropriately during floods, as they often underestimate the risks due to their age and little experience. One way to make young adults aware of flooding is to let them have a vicarious disaster experience, which is the (digital) interaction with others who have experienced a disaster. This research will explore how the combination of a Streamlit interface and a Recommender System can be used to create an interactive story of a vicarious disaster experience, prompting young adults to question their relationship with their environment and what actions they should take to be adequately prepared for floods.

Substantiation

Problem statement

The Netherlands is plagued by the dangers of water. A recent example is the floods in the province of Limburg in 2021, which were caused by rivers bursting their banks. A survey among residents of this area revealed that most of the evacuated residents were not prepared to evacuate and would rather have received information on how to prepare for this earlier (Flycatcher Internet Research, 2021). Furthermore, more than half of the recipients of the NL-Alert emergency messages indicated that they had received insufficient information on how to act in this situation, impairing them to take proper actions.

After humans perceive a risk, they interpret the situation before making decisions, which is known as the process of situational risk perception (Bean et al., 2016). This process is shaped by various factors, including personal characteristics such as age and knowledge of the risk itself (Kuller et al., 2021; Wachinger et al., 2013). Several studies indicated that age affects a person’s experience and knowledge of a flooding (Kellens et al., 2011; Wachinger et al., 2013). The study of Kellens et al. found out that people aged between 16 and 30 tend to underestimate the risks of coastal flooding compared to older people (2011). This can be explained by the fact that people use their prior experience as information on which they base their decision-making (Becker et al., 2017).

A possible way to raise awareness among young adults about the risks of a flooding is to let them engage in vicarious disaster experiences, which is the (digital) interaction with others who experienced a disaster (Becker et al., 2017). Becker et al. argued that vicarious experiences enable people to engage in thoughts and discussions about the experience itself and helps them with understanding the consequences of a disaster, what that means to them, and motivates them in getting prepared (2017). Moreover, it offers the opportunity to let people reflect about the relationship with their environment and how this affects their risk, as they will most likely be confronted with information they had not faced before (Paton & Buergelt, 2019).

Prototype

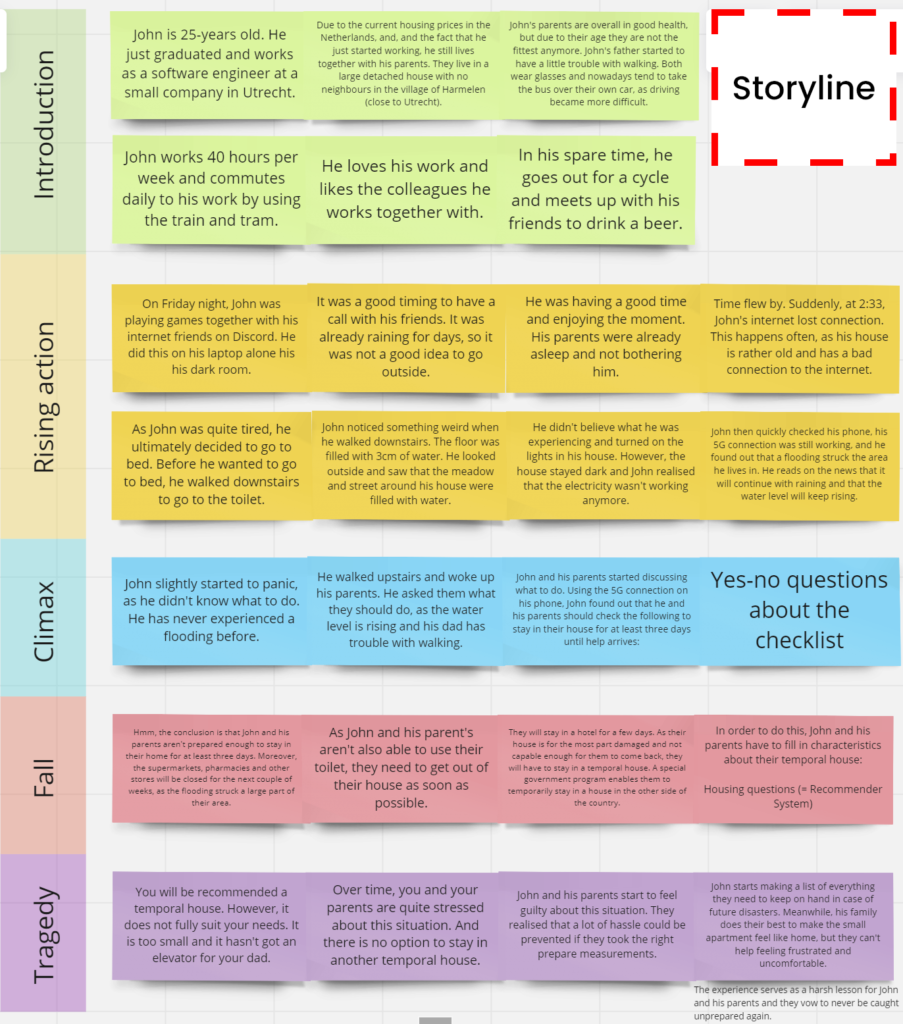

A vicarious disaster experience is created to encourage young adults to better understand how their relationship with their environment affects their risks during a flood. Young adults between 20 and 25 years old are chosen as target audience, as they fit within the range of young people (16 to 30) of the study conducted by Kellens et al. (2011). In order to create the vicarious disaster experience, I devised a story about a protagonist named John, who will experience the consequences of being insufficiently prepared during a flood.

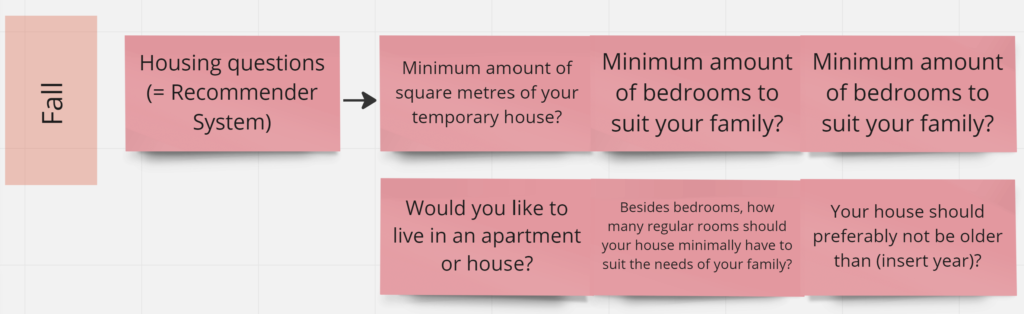

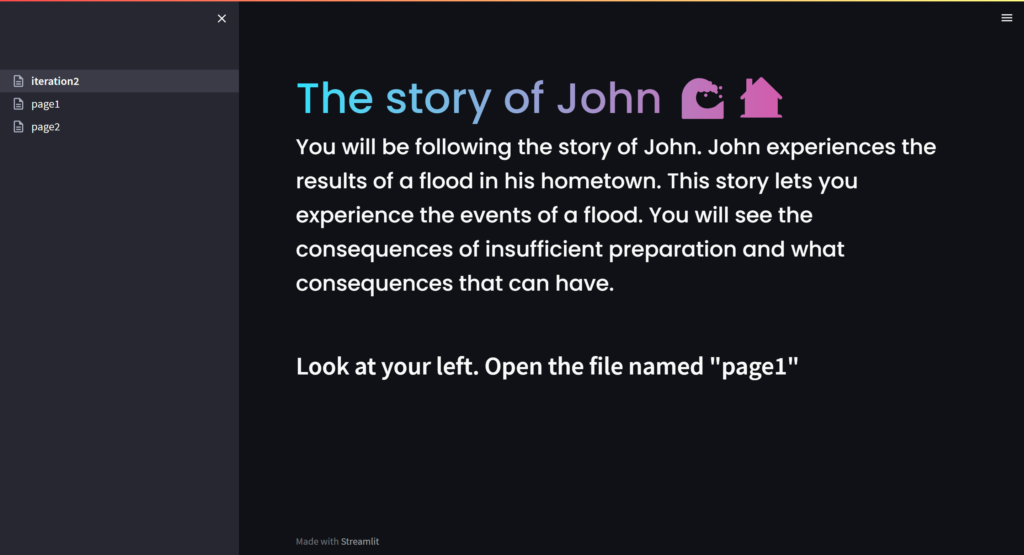

Users can interact with this story by using a Streamlit interface, which enables them to click through the story’s paragraphs. Throughout the story, users must answer questions about John’s relation with his environment in order to let the story continue. The same goes for filling in environmental information of John, which will be used by a Recommender System to generate information that will be used in the rest of the story. These questions prompt users to think about John’s situation and the consequences he experiences currently and in the future.

All my code can be found here.

Iteration 1

This iteration consisted of devising the story, its questions, and building the Recommender System. I decided that the story should end in a tragedy, as Paton and Buergelt argued that the experience of some kind of provocation can question someone’s current situation in a challenging way, ultimately drawing attention to new ways of thinking and acting (2019). Therefore, I used a story structure called Freytag’s Pyramid to devise a story consisting of rising action followed by a point of no return that ends in a tragedy (Reedsy, 2022):

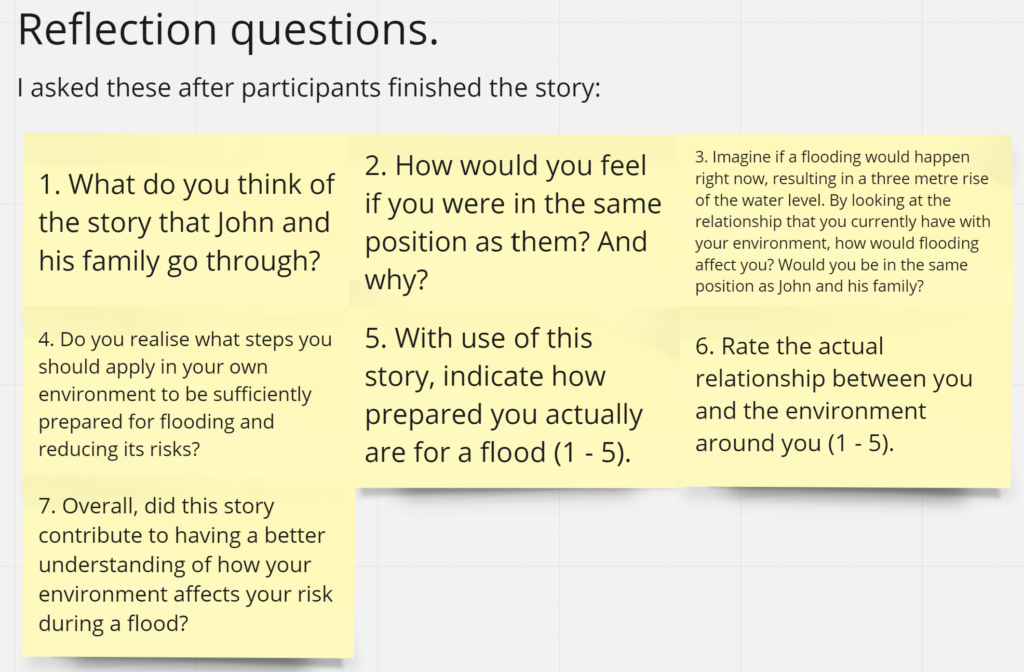

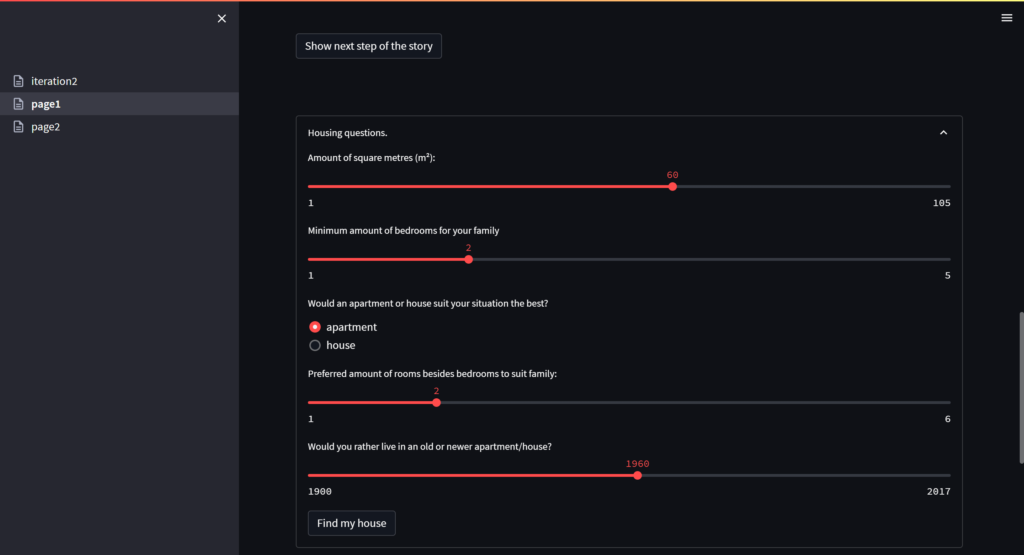

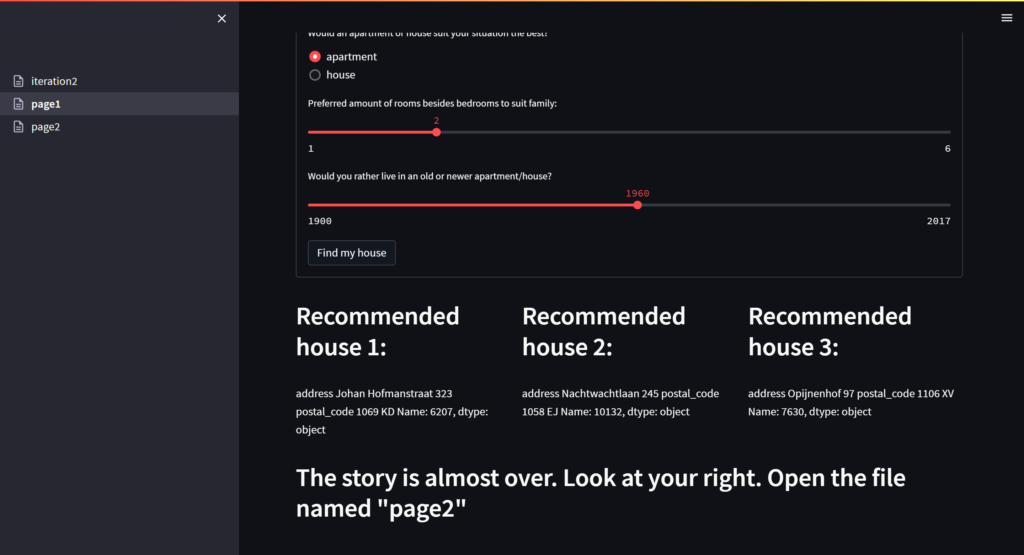

During the story, participants must answer yes-no questions on a checklist to decide if John is prepared enough to stay in his home during the flood. That is not the case, which makes that he must leave, prompting them to use a Recommender System to fill in characteristics about Johns current situation to find him a temporary house. The story and Recommender System had no interface. Four young adults tested this prototype and reflected about their experience. Before and after testing, they indicated how prepared they think they are for a flood, and how much they know about how their environment will affect their risk during a flood. Two Likert scales from 1 (unprepared/no knowledge) to 5 (prepared/much knowledge) were used for this.

Insights:

- All participants indicated that the story gave new insights about events they would not normally think about.

- All participants used the story to reflect on how their current relation with their environment affects their risk. They generated ideas about what to do in order to be prepared.

- Two participants indicated that they know more about their environment than they thought and are probably better prepared for a flooding, making them to increase the scores on their Likert scales. The other two participants decreased their scores.

- Three participants indicated that the story was too much text-focused and missed visuals, making it harder to understand certain parts of the story. Moreover, some of the questions were too straightforward to answer, making them a bit dull.

Iteration 2

I built a Streamlit interface to interact with the story by clicking through its various paragraphs. I also drew doodles that will appear underneath each corresponding paragraph. Radio buttons and sliders are used to interact with the yes-no questions and Recommender System. Moreover, some of the yes-no questions and characteristics to be filled in about Johns current situation have been rewritten to make them less dull. Two young adults tested this prototype.

Insights:

- The doodles and interaction-buttons made it fun to engage with the story.

- The participants lowered their Likert scale scores and mentioned, unlike the participants in iteration 1, to miss specific information on what to do and buy, because they realised they were not adequately prepared.

- One participant found the recommended houses not accurate after comparing his entered information with the recommended houses on Google Maps, making this part of the story a bit unrealistic.

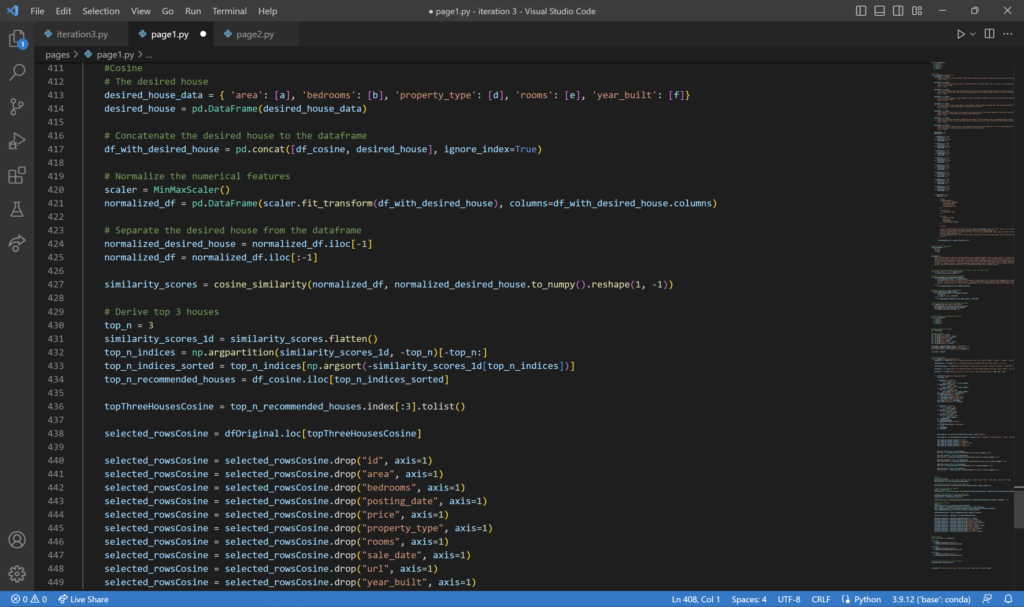

Iteration 3

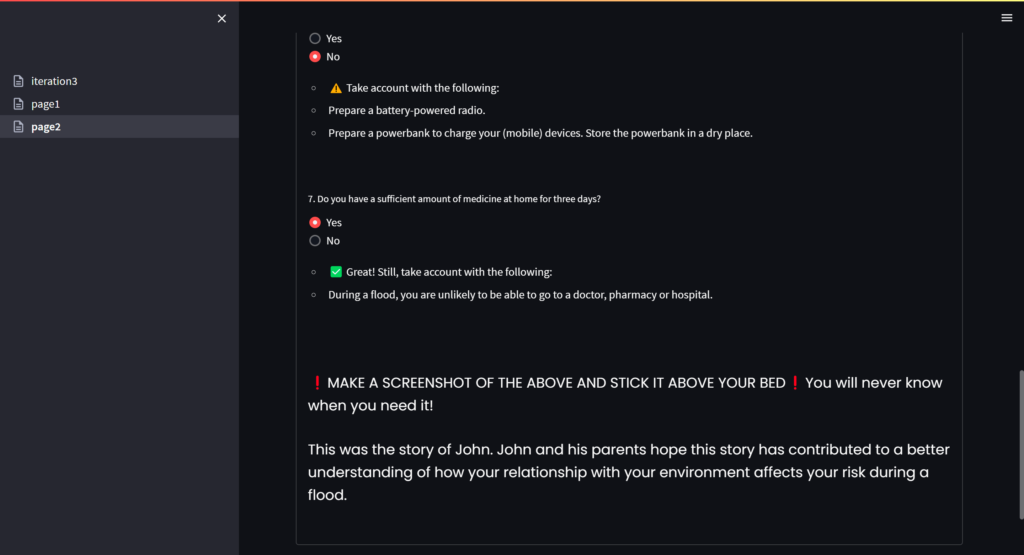

After the story is over, I added a flooding checklist consisting of several requirements. The participants must indicate whether it meets each requirement. Answering yes will display additional information that should be considered. Answering no will show information about how to meet this requirement. Moreover, I changed the Jaccard Similarity to Cosine Similarity to try to make the Recommender System more accurate, as this metric enables to compare the similarity between multiple rows based on numerical data (instead of binary) (Kuntala, 2018). One young adult tested this prototype.

Insights:

- The added flooding checklist was perceived as handy information. The participant lowered his Likert scale scores, but still feels confident about the steps he needs to take in order to prepare himself.

- The prototype can be improved by making it location specific, for example by adapting the flooding checklist based the user’s location.

- The recommended houses can be displayed more detailed, for example by using an iFrame.

Conclusion

Each iteration proved that the storyline prompts users to critically reflect on how their current relationship with their environment affects their risk during a flood, making them to adapt their Likert scale scores. By adding visuals and interaction buttons, the story was experienced as more fun to engage with. Moreover, iteration 2 and 3 showed that participants preferred to add personalised content. This is a way to personalise the story’s impact and what that means for the participants. Future iterations should therefore focus on deriving participant’s data and using it to adapt the content of the storyline, as the story focused mainly on John’s specific situation. Participant’s data can be used to show location-specific tips about coastal or river flooding, or to adapt the dataset of the Recommender System to recommend temporary houses in a safe area close to the participant’s location.

References

Bean, H., Liu, B. F., Madden, S., Sutton, J., Wood, M. M., & Mileti, D. S. (2016). Disaster Warnings in Your Pocket: How Audiences Interpret Mobile Alerts for an Unfamiliar Hazard. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 24(3), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12108

Becker, J., Paton, D., Johnston, D., Ronan, K. R., & McClure, J. D. (2017). The role of prior experience in informing and motivating earthquake preparedness. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.03.006

Flycatcher Internet Research. (2021). Overstroming juli 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.vrzl.nl/application/files/5116/4301/9488/Rapport_onderzoek_overstroming_VRZL.pdf

Kellens, W., Zaalberg, R., Neutens, T., Vanneuville, W., & De Maeyer, P. (2011). An Analysis of the Public Perception of Flood Risk on the Belgian Coast. Risk Analysis, 31(7), 1055–1068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01571.x

Kuller, M., Schoenholzer, K., & Lienert, J. (2021). Creating effective flood warnings: A framework from a critical review. Journal of Hydrology, 602, 126708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126708

Kuntala, R. (2018, September 21). Cosine Similarity and Handling Categorical Variables. Medium. https://medium.com/@rahulkuntala9/cosine-similarity-and-handling-categorical-variables-29f907951b5

Paton, D., & Buergelt, P. (2019). Risk, Transformation and Adaptation: Ideas for Reframing Approaches to Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142594

Reedsy. (2022). Story Structure: 7 Narrative Structures All Writers Should Know. https://blog.reedsy.com/guide/story-structure/

Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C., & Kuhlicke, C. (2013). The Risk Perception Paradox-Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Analysis, 33(6), 1049–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01942.x

The used dataset for my Recommender System can be found on the MDDD Machine Learning Teams channel. (Master Data-driven Design 2022 – 2023 (students) –> B – Fundamentals of Machine Learning –> datasets for exercise –> funda.csv)