Premise

Exploring gamification techniques to increase ADHD students’ self-motivation.

Research

Synopsis

ADHD students experience impairment with self-motivation to execute daily activities. After a student moves out, they encounter many extra activities and temptations. Their former environment where their parents’ structure was automatically provided is gone.

I have ADHD myself and experienced the same impairments after moving out. I did pre-research, conducted interviews, and determined that others shared the same experiences. After that, iterative experiments were started. Therefore, this concept diary explores the possibility of technology, such as gamification, to support ADHD students. Marczewski’s Gamification elements were tried to help motivate the students. Social pressure and responsibility were perceived as helping. A concept was paper prototyped in a co-design session. However, to reduce the amount of work for students, an image classification model was explored with TensorFlow.

ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common psychiatric disorder with restless, impulsive, and unconcentrated behavior symptoms. People with ADHD have impairment with the self-regulation and self-motivation of their day-to-day behavior, such as organization and planning, and starting and achieving (short-term) goals (Barkley, 2015). This hinders patients in college because of the new environment where many extra activities and temptations come along (Jones et al. 1997). Earlier in life, the students could rely on parents to provide the structure (Meaux et al., 2009).

I have ADHD, and I recognize the impairments as it was harder to deal with the symptoms when I moved out. I assumed that more students experienced the lack of structure compared to when they’d live at home, and I wanted to explore how technology could help.

Gamification

Gamification is used to implement game elements in a non-game product or service to motivate activity. There are many possibilities with gamification. To make it more understandable, Andrzej Marczewski created an overview of 52 elements to implement. He also came up with a framework to understand the types of players to design for.

Interviews

I started by conducting three interviews with ADHD students. Two were diagnosed after they moved out, and one started using medication only then. This shows the impact the college transition has on ADHD students. The goal was to understand the impairments other ADHD students experience after moving out to see if there’s a pattern in how they rely on certain things.

Their most prominent impairments are related to self-motivation. The answers varied between getting up in the morning, doing everyday tasks, and weekly routine chores like cleaning the house. The loss of having structured people in the house (their parents) did play a significant role. For example, they felt responsible for getting up and having breakfast with their parents or cleaning their room.

In times of COVID, everybody is more self-reliant. Being accountable for each other may let the student motivate themself to start. Research also shows potential social responsibility to help each other achieve goals (SOURCE). Therefore, it is interesting to learn how students can motivate themselves by performing daily tasks with accountability, like doing their morning routine.

Iterations

Iteration 1

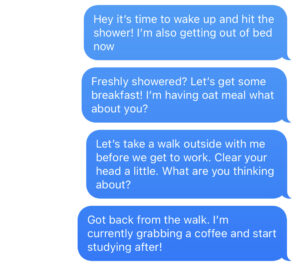

The question I asked myself was: “How can I mimic the same kind of feeling of responsibility in a virtual environment?” Social responsibility is a method of gamification. I assumed that a chatbot was a way to implement this. As chatbots have been shown to have significant efficacy in several psychiatric disorders. A chatbot could lead by example, similar to what parents did, and provide the feeling of responsibility towards students.

Testing

The goal was to test if a chatbot was a suitable medium. Therefore, I had to find out the triggers that people with ADHD need to keep them going.

I tested this concept with a Wizard of Oz method. This is a way to test an idea without first creating a high-fidelity prototype. I played the chatbot myself and sent messages to 3 ADHD students for their morning routine. I knew their schedule and wanted to motivate them to start by leading by example.

Insights

The respondents managed to get out of bed and were motivated. However, talking back to the chatbot costs too much time/focus. I found that the trigger was that someone was watching, which made them feel responsible towards that person, not towards the technology.

Results

I concluded that a chatbot was not a suitable medium, as it did not give the empathy it needed. However, the iteration gave insights about how another person watching them triggers self-motivation. Therefore, the social pressure element of gamification is still a good bet.

People can give more empathy, which could make people feel more motivated. This made me think of a buddy system to make people responsible towards each other.

Iteration 2

This iteration aims to find out if another medium works better to implement social responsibility. I wanted to know if a buddy system would trigger the students more than the chatbot. As a result of the last iteration, I tried to connect friends together. This way, they felt socially responsible toward a natural person.

However, if I would implement this like the last iteration, there are two disadvantages:

- Sending messages to each other takes time in their morning routine, and the first iteration showed; they were not interested in sending messages themselves.

- How can they “prove” that they are really out of bed and doing the things they say with just a message?

I also wanted to know more about what type of users the respondents were to better understand what gamification methods might work.

Testing

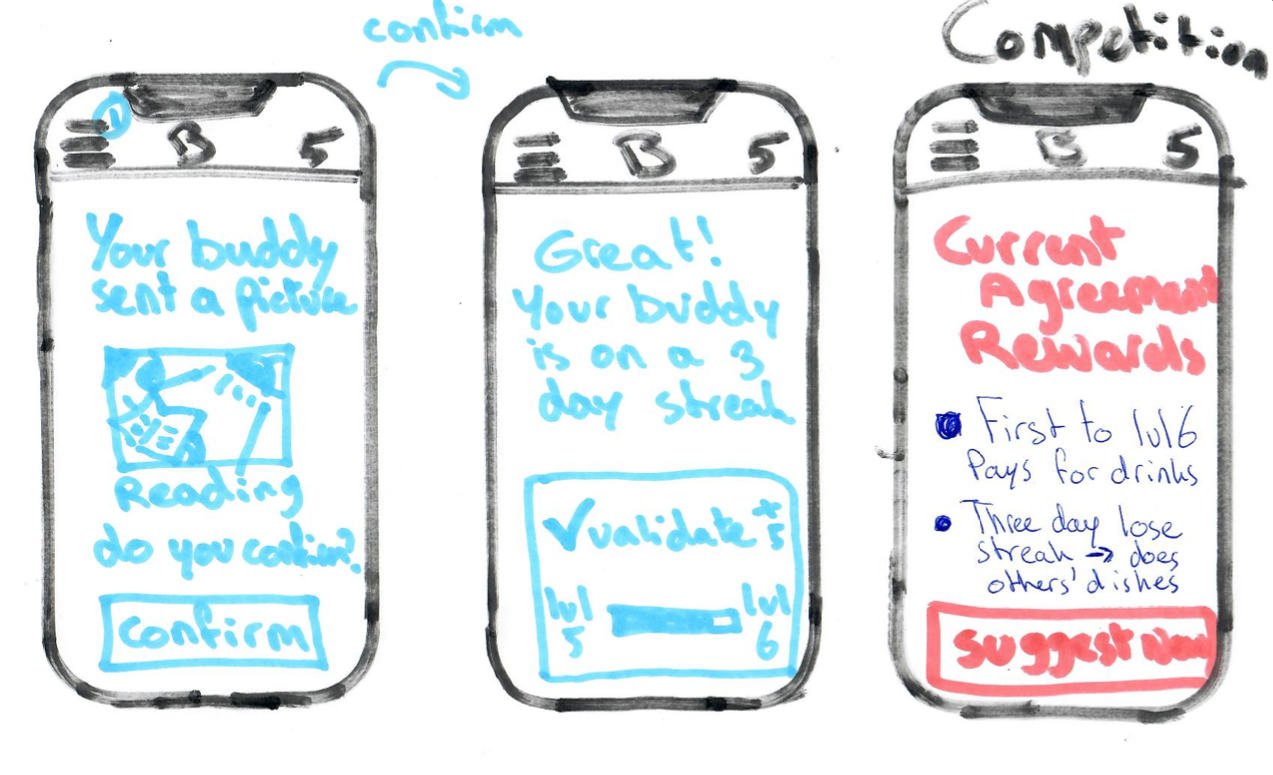

I used the Gamified UK User Type test to discover the types of my respondents. Both of them scored high on the socializer type. Therefore, I tried to expand on the first iteration results and test another trigger by adding the competition element.

The two disadvantages were dissolved by scanning QR-codes that automatically send messages to notify the other. Therefore, it took way less time to execute. They had the same morning routine and scored points when they had scanned the QR code on time. Whoever was the first won.

Insights

The respondents were motivated to get out of bed and score points by doing their morning routine on time. They felt responsible towards the other person and liked the competition element. But they didn’t see themselves using it every morning because it had no specific goal.

Results

The messages sent to each other did their work for now. However, an underlying component was missing to keep using the tool. There are also opportunities in using a collaborative feature.

Iteration 3

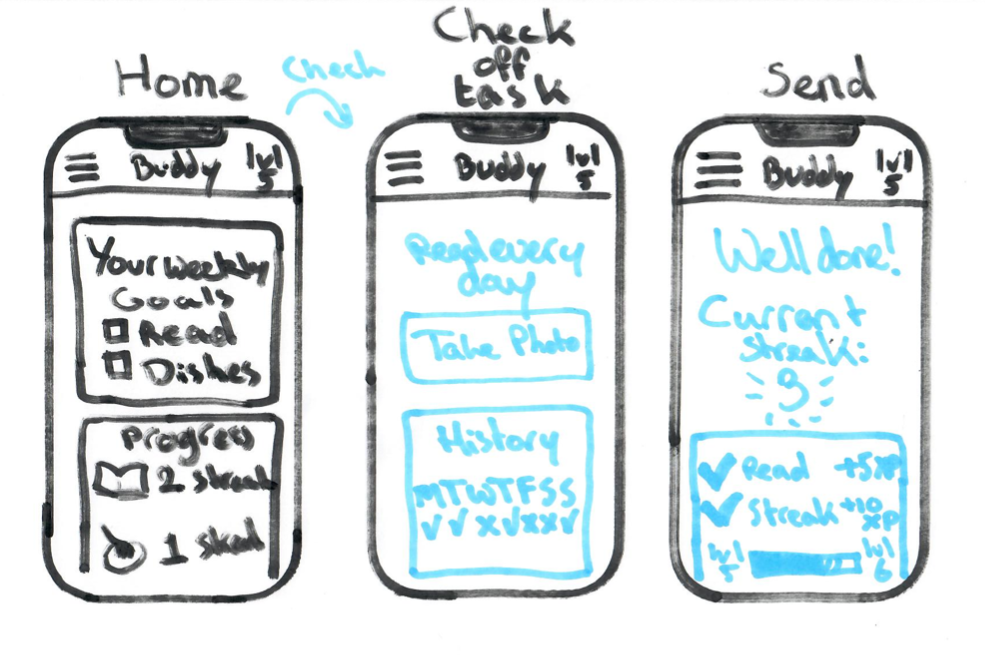

The respondents and I concluded that a concept of social pressure could work, but we wanted to give it more body. I tried the gamification-app Superbetter, and I really liked that the children can earn experience points to level up. This inspired me to use that for the underlying component.

Based on the feedback, I focused on achieving weekly goals instead of morning routines to implement a broader concept. Examples of their weekly goals: Doing the dishes right away and reading daily.

Triggers are: Users should earn XP by achieving goals, social pressure comes from their friends, and they use agreed rewards as an underlying feature. Based on feedback, the competition element was changed for teams.

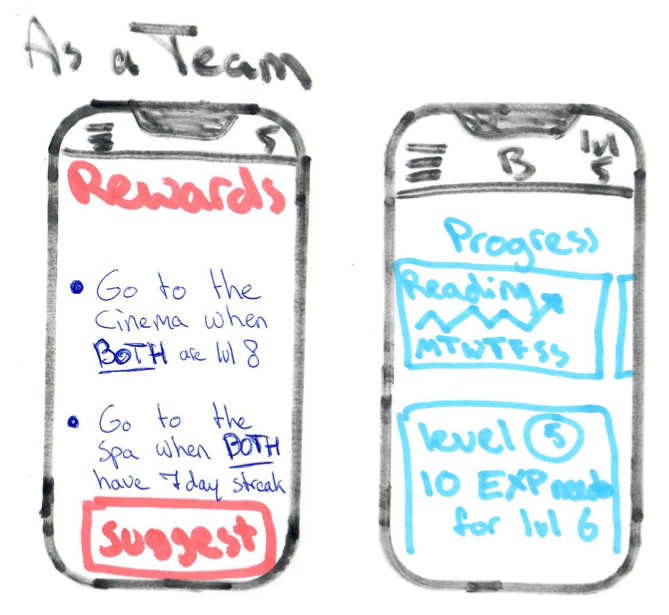

You can earn experience points by sending the other person a photo of yourself doing/having done your expected goal. The other person can confirm the task as a consensus mechanism. If you forget a day, you lose points, and you can earn extra EXP by having things like a streak. The rewards are agreed between the friends (competition or as a team).

We co-created a paper prototype to visualize our concept.

Iteration 4

My respondents didn’t have time to test the new concept. But the motivation came from another element now. Since the students want to spend as little time as possible tracking their activities, I wanted to test if an algorithm could take over the consensus mechanism with image classification. I will try out Google’s TensorFlow, a platform for Machine Learning used for Neural Networks.

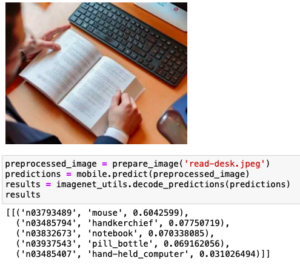

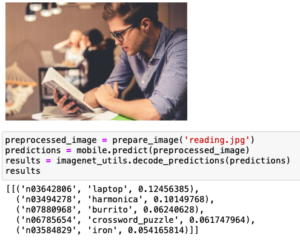

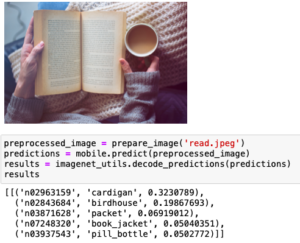

First, I started working with MobileNets in Keras. A model that quickly recognizes images due to its low number of parameters. I had set up the model and tested it.

As you can see, the predictions it made weren’t really on points. Therefore, I decided to try something different and set up my own dataset from GoogleImages to test it.

Final train, validation, and test dataset:

Final train, validation, and test dataset:

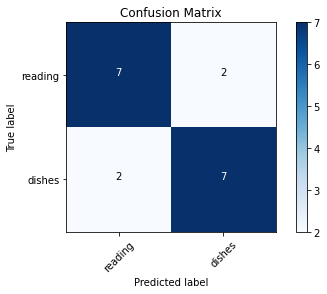

I will try a Convolutional Neural Network model to classify reading and dishes.

Image processing:

I tested the model and got an accuracy of 100%, however, the validation accuracy doing slightly worse means the model is overfitting. However, it could be because of the small test-dataset.

I put the results in the confusion matrix.

Conclusion

I conclude that social accountability shows potential in helping ADHD students with motivation. As an addition, I added social rewards for achieving goals. Further research should focus on how this concept could work long-term with. Another insight is that you have to make it easy to let ADHDers track their process.

Bibliography

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Executive functioning and self-regulation viewed as an extended phenotype: Implications of the theory for ADHD and its treatment. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment., 4th Ed., 4, 405–434.

Chen, Y., Zhang, J., & Pu, P. (2014). Exploring social accountability for pervasive fitness apps. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yu-Chen-309/publication/287832793_Exploring_social_accountability_for_pervasive_fitness_apps/links/580f97af08aef2ef97afe810/Exploring-social-accountability-for-pervasive-fitness-apps.pdf

Jones, G. C., Kalivoda, K. S., & Higbee, J. L. (1997). College Students with Attention Deficit Disorder. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 34(4), 261–273.

Marczewski, A. (2017, February 28). 52 gamification mechanics and elements – gamified UK – #gamification expert. Gamified UK – #Gamification Expert. https://www.gamified.uk/user-types/gamification-mechanics-elements/

Meaux, J. B., Green, A., & Broussard, L. (2009). ADHD in the college student: a block in the road. In Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing (Vol. 16, Issue 3, pp. 248–256). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01349.x