PREMISE

Exploring ways to create an effective stress management method using GSR data and music

SYNOPSIS

Stress is undoubtedly a pandemic by itself. With so many different stressors that we have no control of the only thing we can do is focus on the things that we have control over – our mind and body. There are many proven techniques to manage stress such as exercise or guided mindfulness practice, however, most of them have their limitations and are not easily accessible to everyone. I wanted to find a way that would not only be highly accessible and fun to use but also be evidence-based. I chose to explore ways how we can use GSR biosensor to measure people’s emotional response to relaxing music and recommend them songs that will further enhance their stress reduction effectiveness.

PREFACE

Nobody is immune to experiencing stress, regardless of age, sex, race etc., however, a survey by the American Psychological Association revealed that Gen Z (15-21-year-olds) and Millennials (22-39-year-olds) in the US reported higher than average stress levels and higher than any other generation (APA, 2018). Similarly, a study in the Netherlands found young people to be the biggest population group (82%) at risk of burnout in the past year, a high increase from the previous year (NCPSB, 2022). While the main reason identified for such spike in numbers was Covid-19 related stressors such as job insecurity, financial problems, school-related issues, affected relationships etc. (Graupensperger, Cadigan, Einberger, & Lee, 2021), these and similar issues have been weighing down young people for years before the pandemic. One of the most mentioned causes of stress in young people in the existing research is academic-related.

When stress is not managed it can wreak havoc on a wide range of areas of an individual’s life. According to Hazen et al. (2011), as a response to stress, young people commonly experience anxiety, moodiness and irritability, as well as cognitive issues such as difficulty concentrating, which has a negative impact on students’ academic performance (OECD, 2017). Over time, unmanaged stress paves the way for more serious mental health issues such as depression (Kessler, 2012). Physical health is also at risk, research has shown that stressed people are less likely to exercise and more likely to overeat (Dallman et al., 1993; Stults-Kolehmainen & Sinha, 2013).

One of the most common ways students attempt to manage stress is by listening to music (54.8%), others watch internet videos, talk to friends and even indulge in substance abuse (Mahani & Panchal, 2019). Although there is no data on how popular stress-management apps are among young people, a study found that roughly a half of them were not evidence-based and likely were not effective anyways (Coulon et al., 2016). Given the current state of stress and the highly detrimental consequences it has on young people, there must be a solution that is easily accessible to everyone, evidence-based and engaging. With the currently available technological affordances such as wearable biosensors and an abundance of stress management research in the past decades, there is an opportunity for creating a data-driven solution for this problem.

PROTOTYPING

Building a song database

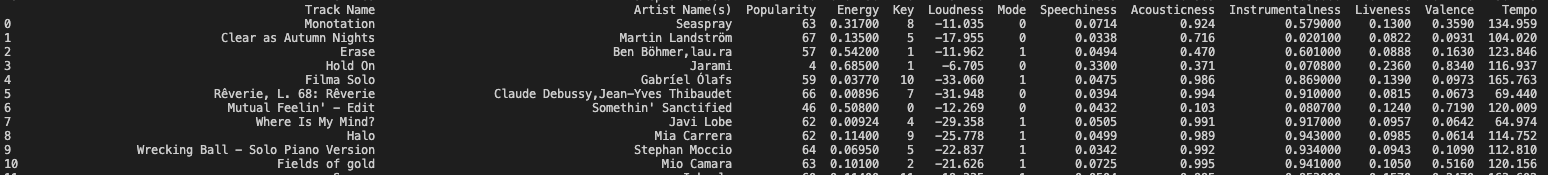

To begin building the prototype, I first needed to have a database with a lot of different potentially relaxing songs. To achieve that, I created a Spotify playlist and added 50 songs that I found in other playlists curated by Spotify (i.e. “Calming Classical”, “Deep House Relax”, “lofi beats”, “Stress Relief” etc.). Then, using Spotistats, I was able to export the playlist data with all the song characteristics such as tempo, genre, valence, acousticness, instrumentalness and many more. After some data cleaning with python, this is what it looked like:

Inducing stress

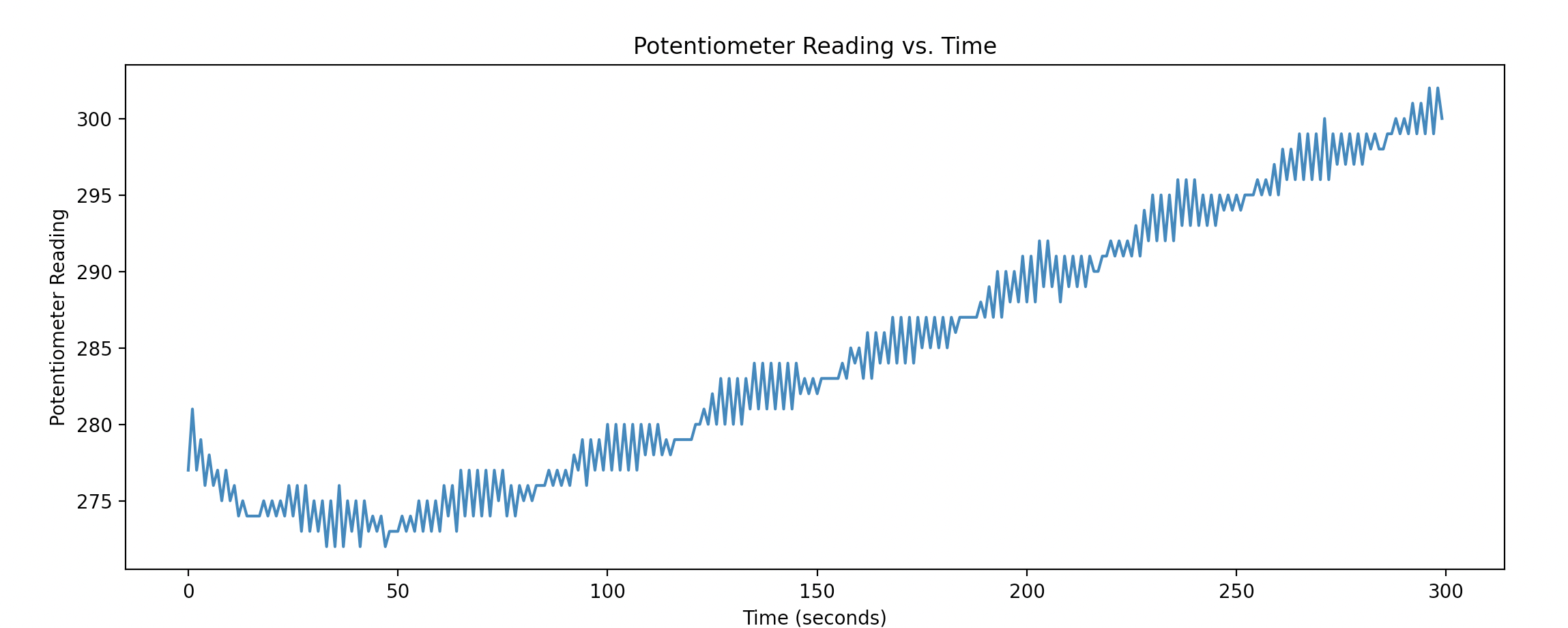

Before I start testing songs on people, I need to make sure they are in a stressed state. After a few unsuccessful attempts to induce stress, I found a method that worked relatively well. It is called the mental arithmetics task. The participant is asked to subtract 7 from 500 and then repeat as fast as possible (500-7, 493-7, 486-7 etc.). Below you can see how well it worked over 30 seconds – the GSR reading went from around 280 to above 300.

Iteration 1

Testing the songs and creating a recommender system

Now that I am able to put the participant in a stressed state, I can start measuring stress. To do that, I started by playing a random song while the participant was wearing the GSR electrodes on their fingers. This is an example of the GSR response to one of the songs:

I repeated the process together with the mental arithmetics task for seven different songs and stored the data in separate JSON files. At this point, I am still not sure what is the best way to make meaning out of all the ups and downs in the GSR data that I collected. Therefore, for the initial version of the recommender system, I simply used the difference between the first (t=0 sec) and last (t=500 sec) GSR values registered, to determine how effective was the song in reducing stress. I added these values ( “before”, “after”, “difference” ) to the data frame for every song I tested on the participant.

Building a recommender system

I now have a data frame with song titles and their features, as well as GSR data indicating how well some of the songs worked on the testing participant. Below you can see that the song called “Hold On” worked the best out of the other few that I tested. It decreased the GSR by 67 units.

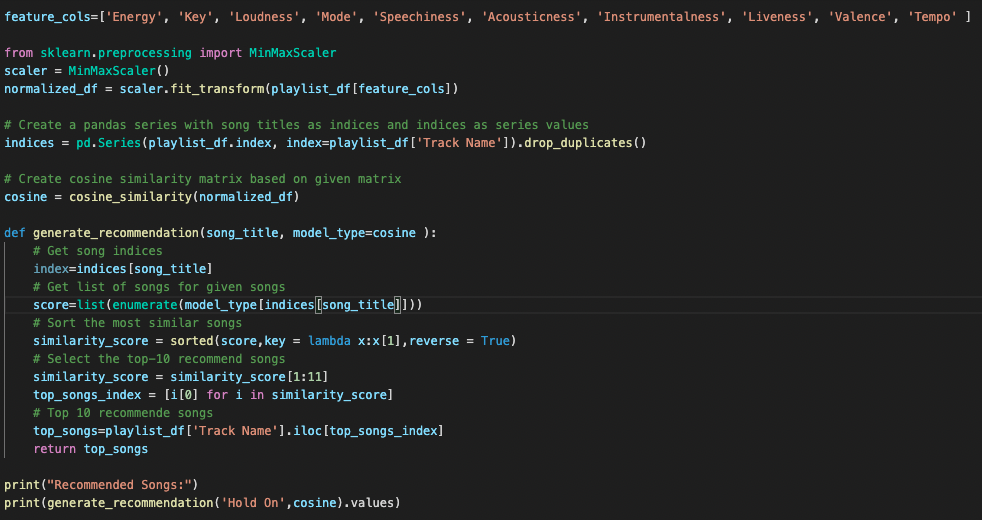

Now I want to build a recommender system that will be able to recommend the user songs that are similar to the one that performed the best. This type of recommender system is called content-based filtering. I will be using a cosine similarity machine learning model, which compares the similarity of two feature vectors. The first step is to select the features I want the recommender system to base its recommendation off and transform them into the range between 0 and 1. I did it using MinMaxScaler from sklearn and used the following features: ‘Energy’, ‘Key’, ‘Loudness’, ‘Mode’, ‘Speechiness’, ‘Acousticness’, ‘Instrumentalness’, ‘Liveness’, ‘Valence’, ‘Tempo’. Then using the sklearn’s cosine_similarity library and the code I found and adapted from machinelearninggeek.com, I was able to generate a list of top 10 songs from the database that were the most similar to “Hold On” (the one that performed the best so far).

Iteration 2

Testing the recommendations with an app interface

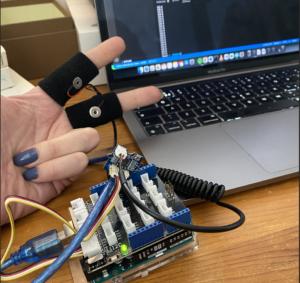

Then l tested the first couple recommendations to see how they performed. In addition, I created an interface for the music player with the recommender system, which I also tested out with the user. One feature of the interface is seeing your GSR numbers in real-time. I personally like seeing them because it helps me concentrate on relaxing and my breathing, however, I can imagine that for some people it might be stressful to watch them, especially if the numbers are increasing. Unfortunately, I was not able to implement this feature into the design due to my limited time and skills. Therefore, I tested this feature by asking the participant to watch the live numbers on the serial monitor of Arduino IDE on a laptop.

The top two recommended songs were “Romeo” and “Mutual Feeling”. The first song performed relatively well with a decrease of 28 units, however, the second only showed a decrease of 7. However, this is not surprising since the dataset is very small. Regarding the interface, the participant prefered not to see the real-time data for the reason that I suspected, it was too distracting.

Iteration 3

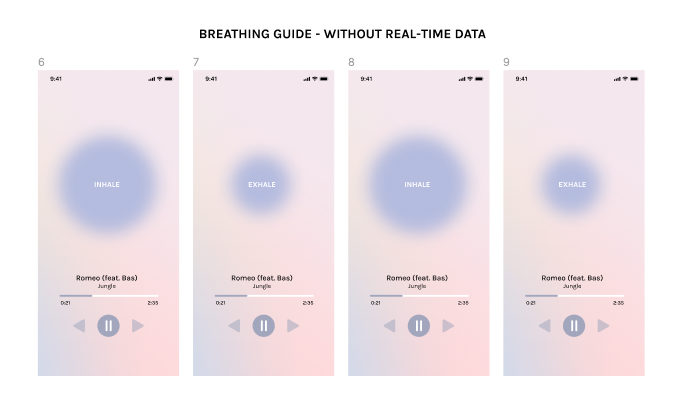

Although there is evidence that specific genres and types of music will have a universal relaxing impact on one’s body, a number of studies have also shown that when exposed to one’s preferred genre of music, the indicators of relaxation can significantly increase and anxiety may decrease compared to when exposed to other unfamiliar music (Bernardi, 2005; Salamon, 2003). Therefore, for the third iteration, I decided to let the user choose their own relaxing song that they are familiar with. In addition, I changed the interface based on the user feedback and enabled an option to hide real-time data. Also, to improve the user experience and the effectiveness in stress reduction, I added a breathing guide that tells the user when to inhale and exhale. Such diaphragmatic breathing can significantly reduce stress after just a single practice (Arsenio & Loria, 2014). Although I was not able to implement it due to time and skills limitations, I imagine it to send light vibrations via the phone or a wearable device indicating when to inhale or exhale. However, I asked the participant to take deep breaths during the listening session.

The participant chose a song that they personally find relaxing and listened to it while taking deep breaths. The song performed rather well, GSR went from 280 to 230 in the first 40 seconds, likely due to the deep breathing too.

REFLECTION AND CONCLUSION

Overall, the process of testing GSR in response to music turned out to be trickier than I thought. It is difficult to ensure the participant is in a stressed state over and over again as they become habituated to the stressor. There are so many other factors that should be accounted for to ensure accuracy in testing, such as room temperature, testing time etc. After doing the experiments, GSR seems to be quite an appropriate indicator of one’s emotional arousal in response to music, however, it would be more powerful if it was combined with other biosensors such as HR monitor. The recommendation system should be tested further with a larger and better organised data set but I think having quite an extensive variety of song characteristics to train it with was very helpful. Lastly, incorporating breathing techniques proved really effective in reducing stress. There is potential to make it even more engaging and data-driven by combining the breathing guide with HR data.

REFERENCES

APA. (2018, October). STRESS IN AMERICA<sup>TM GENERATION Z</i>. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2018/stress-gen-z.pdf

Arsenio, W. F., & Loria, S. (2014). Coping with Negative Emotions: Connections with Adolescents’ Academic Performance and Stress. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2013.806293

Bernardi, L. (2005). Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory changes induced by different types of music in musicians and non-musicians: the importance of silence. Heart, 92(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.064600

Coulon, S. M., Monroe, C. M., & West, D. S. (2016). A Systematic, Multi-domain Review of Mobile Smartphone Apps for EvidenceBased Stress Managementsa. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.026

Dallman, M. F., Strack, A. M., Akana, S. F., Bradbury, M. J., Hanson, E. S., Scribner, K. A., & Smith, M. (1993). Feast and Famine: Critical Role of Glucocorticoids with Insulin in Daily Energy Flow. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 14(4), 303–347. https://doi.org/10.1006/frne.1993.1010

Graupensperger, S., Cadigan, J. M., Einberger, C., & Lee, C. M. (2021). Multifaceted COVID-19-Related Stressors and Associations with Indices of Mental Health, Well-being, and Substance Use Among Young Adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00604-0

Hazen, E. P., Goldstein, M. C., Goldstein, M. C., & Jellinek, M. S. (2011). Mental Health Disorders in Adolescents. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Kessler, R. C. (2012). The Costs of Depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 35(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005

Mahani, S., & Panchal, P. (2019). Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Stress Management among Undergraduate Medical Students at Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2019/41517.13099

NCPSB. (2022). AD: Tachtig procent van jongeren zit door corona tegen burn-out aan. Retrieved from https://nationaalcentrumpreventiestressenburn-out.nl/ad-tachtig-procent-van-jongeren-zit-door-corona-tegen-burn-out-aan/

OECD. (2017). Most teenagers happy with their lives but schoolwork anxiety and bullying an issue. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/most-teenagers-happy-with-their-lives-but-schoolwork-anxiety-and-bullying-an-issue.htm

Student Development, 51(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0108

Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Sinha, R. (2013). The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 81–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0090-5

Read more "Combining GSR data and music to reduce stress" This course started with a few Arduino workshops which enthused me to try to work with Arduino. At first, I did some research into Arduino compatible sensors. I inspired my research on the

This course started with a few Arduino workshops which enthused me to try to work with Arduino. At first, I did some research into Arduino compatible sensors. I inspired my research on the